and the Golden Age of Television

Mad Men” concluded its storied run on May 17 after 92 episodes, thousands of cigarettes, hundreds of cocktails, and coverage of 11 of the most turbulent years in our nation’s history. It will likely be looked upon as the final act of the so-called “Golden Age of Television.” But was it a happy or tragic ending? Like the conclusions of “Breaking Bad” and “The Sopranos,” it depends on how you define those terms.

Can a show with nearly 100 hours of plot that listed 25 different regular characters and 70 supporting characters sufficiently tie up narrative threads? More importantly, should it even be attempted? And, if so, is there some edict that demands it end happily?

Did I want happiness for these characters? Maybe not saccharin sunshine, but after the trials we’ve seen these generally good people go through, yes, I did — even for the slick Pete Campbell (Vincent Kartheiser), the closest thing to an antagonist the first season had. But I didn’t expect creator Matthew Weiner to allow it. Imagine my surprise when watching “Person to Person,” the series finale, as I saw character after character find happiness. But this wasn’t storybook happiness. This was happiness for now, happiness with varying degrees of personal loss (children, careers, spouses, etc.) that leads to a slightly more contented state in the waning months of 1970. There are enough hints at new successes professionally (Joan, finally in the role she’s always been meant for — the boss) and personally (Peggy and Stan!) to fuel another 10 years of hypothetical plots, and that satisfies me.

Click on the image to take the Mad Match challenge.

Do they find success? Is that the big question? Weiner made it clear: it’s not about success. Don Draper, who can pitch you 20 winning tag lines before his first morning Old Fashioned, has never lacked for that. But self-fulfillment? That’s been the goal.

Can Don Draper (played with consistently spackled over emotional baggage by Jon Hamm) change? Can he be happy? Can he allow himself to be loved? These are questions that are much harder to answer. That was Don Draper’s — and by extension, Weiner’s — challenge: Did it work? Would everything Don’s been through — the drinking, the affairs, the professional highs and crippling lows, the consistent loss of each new family he established, lead to self-fulfillment? Or, as many insisted the opening credits spelled out, would Don’s end be a sharp, precipitous fall with all of his second chances finally used up?

As Weiner, who wrote or co-wrote an astonishing 72 of the series’ 92 episodes, played out in the final string of episodes this spring, the argument that Don seemed destined to spiritually fail and repeat his mistakes in perpetuity gained credence as he found himself stripped of everything that made him Don Draper (an identity that was the careful construct of a decades-long charade). With no job and no family, he began a crash course to the one place he ever found any sort of spiritual rebirth in the past: California.

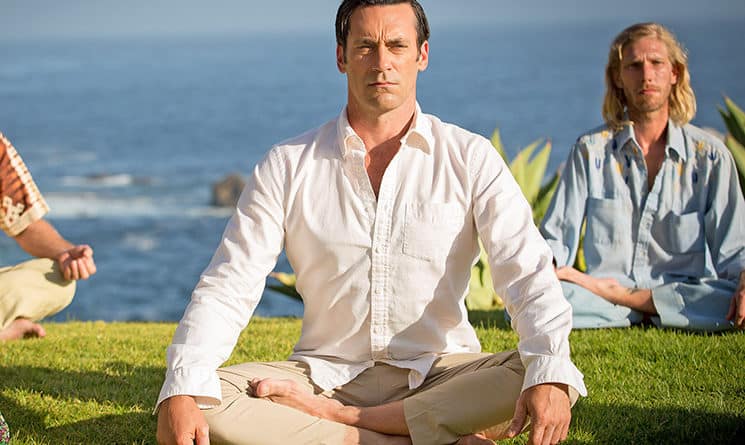

With Draper literally trapped at a meditation retreat, he’s given two basic choices: continue destructively through another decade or change.

With Draper literally trapped at a meditation retreat, he’s given two basic choices: continue destructively through another decade or change. In a group therapy session, an unassuming man tells his story. He has a good job and family. And yet he feels that he simply sits on the shelf, ignored and unloved. In a transformative scene for both the character and Hamm, Don realizes the red-blooded, Sunkist-drinking, Hershey-eating, Chevy-driving American ideal he sold in pitch after pitch is even more hollow than he already thought. More hollow even than himself, a deeply-traumatized orphan who could never successfully show or receive love. Is it too late for him?

My reading of the sure-to-be-debated finale is that no, it was not too late for Don. He finally accepted someone else’s pitch. At the retreat, the meditation leader intones, “The new day brings new hope. The lives we’ve led. The lives we’ve yet to lead. A new day, new ideas, a new you.”

What follows potentially sets Don up as a changed man who finds renewed energy alongside a renewed career that begins with his implied involvement in one of the most famous commercials of all time. It may seem that using his last chance at self-fulfillment as an avenue for pitching Coca-Cola by extolling the virtues of perfect harmony and calling something with high fructose corn syrup “The Real Thing” is crass and far from a happy ending. But, as Stan tells Peggy, “You have such a rare talent. Stop looking over your shoulder at what other people have.”

If Don can harness his talent and his happiness, he can teach the world to sing about any product he wants. Is this a happy ending? For some. It is for me. It is for Don. It is for Weiner. And it is for the Golden Age of Television.