Sen. Marco Rubio’s face was recently seen on the side of a bus barreling along Route 101. Fellow Sen. Ted Cruz made stops in Rochester and Rye on his five-day whirlwind tour of the state. Donald Trump was at Portsmouth Toyota with former U.S. Sen. Scott Brown on Jan. 16. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s daughter, Chelsea, rallied with local Democrats at the Portsmouth Brewery last Tuesday, Jan. 12. And fringe candidate Vermin Supreme attended a potluck dinner at the Ten Rod Farm in Rochester on Friday, Jan. 15, his signature pony in tow.

If your phone is ringing more than usual, if the junk mail is piling up, and if strangers are knocking at your door each weekend, chances are it’s election season and the New Hampshire primary is on the horizon.

New Hampshire loves to vote, and its first-in-the-nation presidential primary, held this year on Feb. 9, is our Super Bowl. We love the event so much, in fact, that the state has officially commemorated its centennial. As politicians, commentators, and voters look back on the primary’s history, it’s surprising that the contest we know today is a relatively new innovation. And the way New Hampshire voters select presidential candidates may continue to evolve in the decades to come.

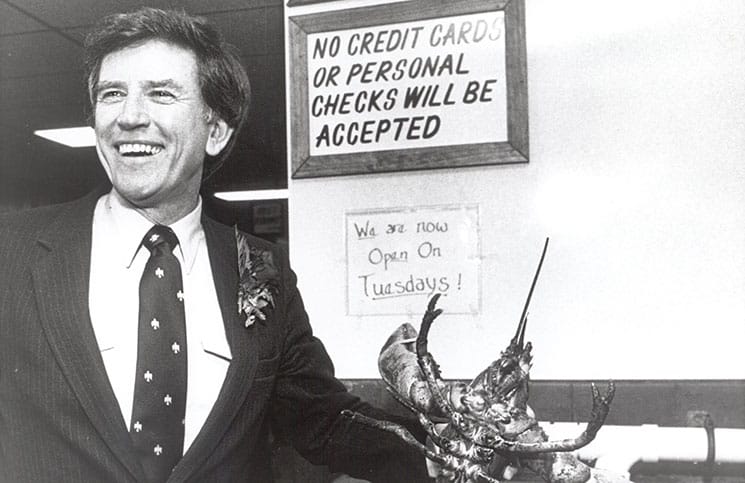

Sen. Gary Hart campaigns in New Hampshire during the 1984 primary. photo courtesy of the New Hampshire Institute of Politics & Political Library at Saint Anselm College

Primary origins

You have state Rep. Stephen A. Bullock to thank for New Hampshire’s move to direct voting for presidential candidates. Before 1916, the state had a short-lived caucus, and political party bosses in the Granite State had final say over which candidates won. Bullock’s legislation allowed residents to select the delegates for each party. The first New Hampshire primary, held March 14, 1916, wasn’t the first in the nation at the time — Indiana had us beat by a week, and Minnesota held its contest the same day. By 1920, however, changes in the other states’ primary schedules left New Hampshire decisively first.

For its first few decades, New Hampshire’s primary was a relatively low-status contest. But it quickly rose in prominence in 1952 thanks to the perfect alignment of politics and the innovation of television, according to Andrew Smith, a University of New Hampshire professor and director of the UNH Survey Center. Smith recently co-authored the book, “The First Primary: New Hampshire’s Outsize Role in Presidential Nominations.” It’s one of two new books from Seacoast authors about the primary — former N.H. Republican Party chairman Fergus Cullen, a Dover resident, recently released “Granite Steps,” a look at the primary’s last 20 years.

In 1952, voters could cast a non-binding vote for their candidate of choice, as well as vote for their preferred delegates. Known as “the beauty contest,” it boosted Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s candidacy and influenced then-President Harry Truman’s decision not to seek a second term.

“Similar to today, television news was always looking for content,” said Smith. “They covered the quirky primary and at the same time there were some interesting races. … It was the first primary to put New Hampshire on the map.”

Candidates began to realize the influence New Hampshire could have on the national presidential race in 1968, when Gene McCarthy beat expectations against President Lyndon Johnson — which, in turn, prompted politicians to start visiting the state years before an election.

National politicians weren’t the only ones who saw the primary’s potential to influence the rest of the nation. In the 1970s, a young state representative from Portsmouth made it his mission to protect New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation status as a way to raise the profile of the growing opposition to the Vietnam War.

“I saw there was a real value of having New Hampshire come first,” said Jim Splaine, Portsmouth’s assistant mayor and a former state representative. “It became clear the role of the New Hampshire primary was good at letting people speak and, in this case, stop a war.”

A bill he sponsored to put New Hampshire one week ahead of any other primary or similar event was adopted in 1975, and Splaine has since sponsored half a dozen pieces of legislation freeing the state to put its contest even before the Iowa caucuses.

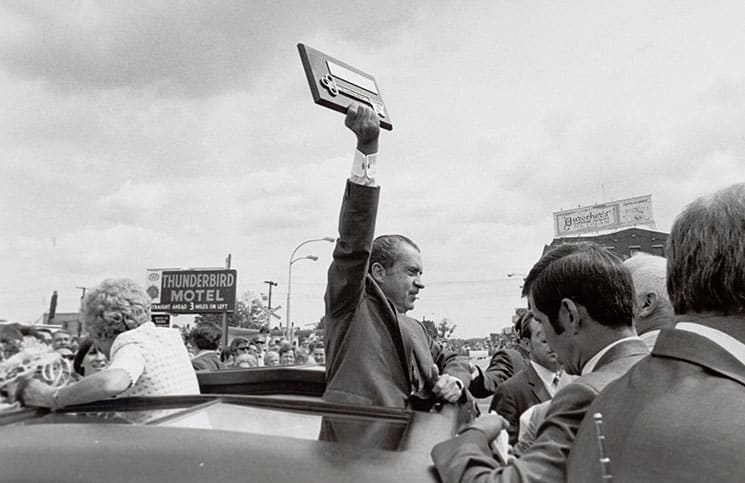

President Richard Nixon campaigns in Nashua in August 1971. photo courtesy of the New Hampshire Institute of Politics & Political Library at Saint Anselm College

The legislation has proven to be key in giving N.H. Secretary of State Bill Gardner the power to resist efforts by the national political parties to strip New Hampshire of its first-in-the-nation status.

“1984 was the most severe threat,” said Gardner. “Nancy Pelosi (then a member of the Democratic National Committee) came here to say if the primary was going to be on the day I said, the state would not be allowed any delegates at the national convention. … I explained to her there was a state law and I was complying with the law and she said it was not a similar election.

“A week before the primary, the DNC sent out a press release saying this event New Hampshire is having is illegitimate,” said Gardner. Despite a blizzard and threats from the national party, the primary went on as planned. “About four months went by and the DNC put out a press release saying, ‘last call for New Hampshire to host an event to get into the convention.’ Then nothing happened and three weeks before the convention we got a call saying, ‘We didn’t mean any of it.’”

An electorate in flux

When the national media comes to town, they often bring with them stale assumptions about the New Hampshire electorate — that we are bedrock Republicans with a stubborn independent streak. Smith says none of these assumptions have ever proven to be true in the modern era. New Hampshire’s electorate is hard to define, largely because it has drastically changed in the past 15 years. Between 2000 and 2008, one-third of New Hampshire’s electorate was new — either voters who turned 18 or recent Granite State residents. Since 2008, 30 percent of the electorate again has changed.

“Obviously, not all of those new people are going to vote and may vote the way the older people did, but you can’t make assumptions that the electorate is the same,” said Smith.

Campaigns and the media also bank heavily on wooing independent voters, but Smith warns that most people who claim independence actually have an affiliation with one party or another.

“People who are truly independent don’t pay attention to politics and don’t vote,” said Smith. “You’ve got to win your party’s registered voters to win. No candidate has won without the plurality of the party’s voters.”

What the national media can rely on each election cycle is that New Hampshire voters will wait to make up their minds.

“Roughly a month before the 2008 primary, so the beginning of December in 2007, (former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt) Romney had a 32 to 19 lead over (Sen. John) McCain and (former New York Mayor Rudy) Guliani. That’s as big of a lead as Trump has right now,” said Smith. McCain wound up winning that primary and went