In the White Mountains years ago, after looking up at the Old Man of the Mountain and hiking down into the Flume Gorge, tourists might have stopped by a souvenir shop for a way to remember it better. Before everyone had a camera phone, before any color photography, chances are the image they brought home was taken by Charles Sawyer.

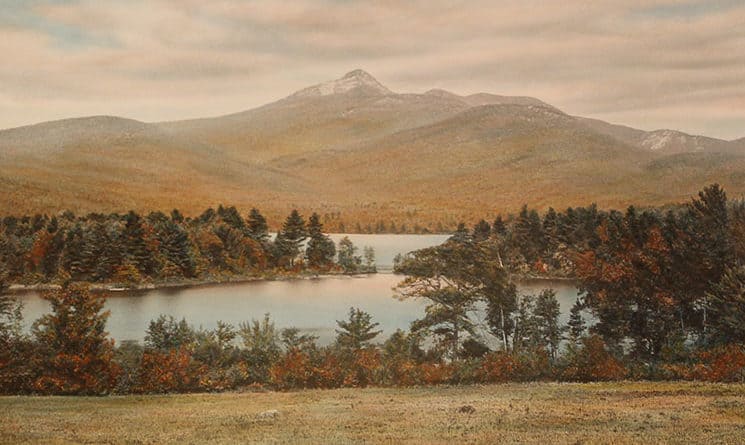

Carol Gray remembers his postcard-sized prints of Echo Lake still lingering in some of the shops when she was a child. It was one of Sawyer’s favorite scenes to capture during the golden years of hand-painted photography, roughly 1900 to 1940.

“For tourists, they took home more than a memory. They took home something tangible, something concrete to remind them of where they’ve gone – a place in nature that was peaceful and eye-appealing,” Gray said. “In most cases, he was trying to capture the beauty in nature.”

Gray, author of “The Hand-Painted Photographs of Charles Henry Sawyer,” is presenting a talk on April 16 at 1:30 p.m., as part of an exhibit of Sawyer’s work in the Keefe House Gallery at the Woodman Museum in Dover. The exhibit continues through June 5.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Gray rediscovered Sawyer. She accompanied a friend to an auction of work by Wallace Nutting, perhaps the most popular name in hand-painted photography. She started looking in antique stores for these collectable prints when she saw one by Sawyer. “In my estimation, the coloring was better,” she said. “I really liked it.”

Sawyer spent some time learning to paint black and white photographs under Wallace Nutting, before opening his own studio in Farmington, Maine, in 1904, and eventually settling in Concord, to be closer to the White Mountains in the 1920s.

Gray, who grew up in Maine and lives in Nashua, spent several summers researching Sawyer and collecting his work. The exhibit at the Woodman features more than 50 of Sawyer’s photographs of Maine and New Hampshire, including some that Gray is selling. She is one of the curators, along with Thom Hindle and John Peters.

Sawyer, who lived from 1868 to 1954, used large wooden cameras and glass plate negatives to photograph landscapes. A period camera, examples of Sawyer’s original negatives, and tools used in the painting process are also on display.

Before color film, hand-painting photographs made them more vibrant and true to life. Gray said her mother used to paint baby photographs, and some things can’t be appreciated any other way. “How can you see a sunset in black and white?” she said.

Vintage packs of souvenir photographs, once sold to tourists for 25 cents.

For many photos, Sawyer kept precise notes on sunlight, colors, and camera settings. Gray said he even scribbled a profanity once when the wind shifted after he had so carefully set up a shoot. But he didn’t always feel compelled to paint the photographs exactly as he documented them. He would sometimes remove signs of modern life like utility poles, and he changed one scene from morning to evening, she said.

Sawyer believed his customers wanted landscapes that were not just pleasant, but also interesting and familiar, real places that had touched their souls, Gray said.

His prints were an affordable way for people to buy art as keepsakes, and he was successful in both his artistic endeavors and business career. He sold thousands for around a dollar each, and rare ones in good condition can be worth a few hundred now.

Like Nutting, Sawyer hired several colorists to fill demand, and his work could be considered commercial. But his photographs weren’t staged, and most of the creative work was in selecting subject, studying camera vantages, waiting for the right light, framing compositions, and paying attention to the movement of shadows. His legacy is not just as a leader in a photographic movement, but more importantly, in promoting and preserving the beauty of rural New England and it’s natural wonders.

The hand-painted photography industry faded in time, as did many of the photographs themselves, making them more rare and valuable. The Woodman Museum is celebrating its centennial season, and some of the images it’s showing are just as old. But because Sawyer believed “only really good pictures give permanent satisfaction,” they are timeless.

The Keefe House Gallery is located at 15 Summer St., behind the Woodman Museum in Dover. See woodmanmuseum.org.